Bucknell's Lower Co-authors Study Finding Climate Change's Impact on Firefly Population

April 29, 2024

Fireflies captured during the 2019 PA Firefly Festival. Photo by Carla Long

Your eyes aren't deceiving you; some firefly species may be declining due to environmental forces. Now a team of researchers — including Bucknell University Professor Sarah Lower, biology — have analyzed data from the citizen science program Firefly Watch and machine learning models to find that climate change may pose a greater threat than previously thought to firefly populations.

"One of the top things I've heard in the audience at firefly festivals is about how people are not seeing as many fireflies as they used to," Lower says. "This meta-analysis gets to the data and the reasons for that observation in some species."

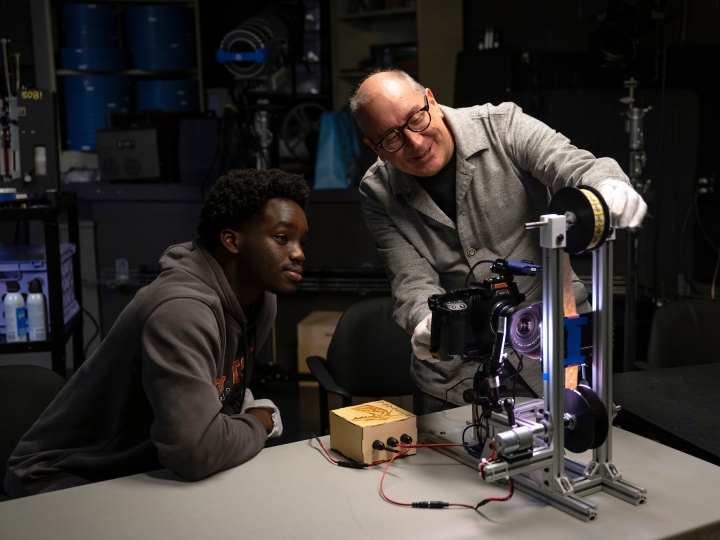

Professor Sarah Lower, biology, participates in firefly collection. Photo by Carla Long

Lower collaborated with Darin McNeil, the lead author, assistant professor, forestry and natural resources at the University of Kentucky; Sarah Goslee and Melanie Kammerer of the United States Department of Agriculture – Agricultural Research Service, Pasture Systems and Watershed Management Research Unit at University Park, Pa.; and John Tooker and Christina Grozinger from the Department of Entomology, Insect Biodiversity Center, Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, on the research. They used machine learning models to analyze more than 24,000 Firefly Watch surveys. Their study, published in Science of the Total Environment, identified the factors likely responsible for troubling declines in firefly populations across North America.

The researchers trained machine learning models to evaluate the relative importance of a variety of factors within the data collected on firefly populations, including pesticides, artificial lights at night, land cover, soil/topography, short-term weather and long-term climate. Their analyses revealed that firefly abundance was driven by complex interactions among soil conditions, climate/weather and land-cover characteristics — with climate change and habitat loss having the greatest impact.

Due to the impact that climate and weather conditions have on firefly abundance, they concluded that there is a strong likelihood that firefly populations will be significantly influenced by climate change, with some regions becoming higher quality and supporting larger firefly populations, and others potentially losing populations altogether.

"We're the first to show a whole myriad of factors that drive firefly populations," McNeil says. "The machine learning models we used let us look at the relative difference of factors. Climate is one of the major drivers. It's more important than other factors. The fireflies may be more sensitive to climate change than we previously thought."

The researchers also found that other factors — especially land-cover characteristics and landscape context — remain strong predictors of firefly abundance in the eastern United States.

They conclude that future conservation of North American firefly populations will depend upon:

- Consistent and continued monitoring of populations via programs like Firefly Watch (Mass Audubon) and Firefly Atlas (Xerces Society)

- Efforts to mitigate the impacts of climate change

- Insect-friendly conservation practices

Given that many firefly species are habitat specialists, the researchers write that species-specific monitoring efforts — either via citizen science or biologist-led censuses — would also help provide greater detail on the habitat patterns revealed by their analyses and address the risks to individual species.

"Each species has its own habitat requirement and things it needs to succeed," Lower says. "With the citizen science data in this study, we're looking at fireflies in the aggregate, but we would like people in citizen science to get more training in species identification. If we can get species-level information, we can provide more specifics on species living in a particular area and how best to protect them."

Still, the new study is the first to address some specific reasons fireflies persist in some places, but not others, in hopes of conserving firefly populations.