Curing What Ails Us

April 17, 2015

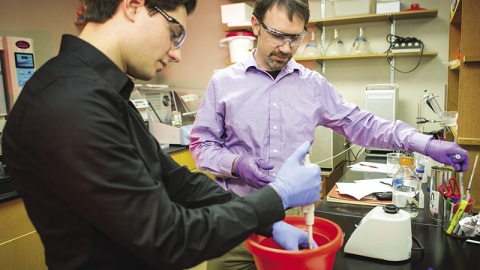

Professor Dave Rovnyak, chemistry, and graduate student Matt Miele analyze samples of human serum.

The Human Health Initiative allows Bucknell students and faculty to team up with medical professionals for research opportunities — and for the greater good.

Two years ago, central Pennsylvania families seeking diagnoses of autism spectrum disorders faced a yearlong wait to see a pediatric specialist at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville. That’s an eternity to worried parents, and a loss of precious treatment time for their children.

“When you have a child and you sense something is amiss, it’s terrifying and upsetting and confusing,” says Gary Sojka, Bucknell president emeritus. “You have to live this to understand it fully.”

Today the waitlist is down to zero, thanks to the Geisinger-Bucknell Autism & Developmental Medicine Center in Lewisburg. Sojka and his wife, Sandy, whose late son had developmental disabilities, are donors who serve on the advisory board of the center, where undergraduates work alongside medical professionals in the diagnosis and treatment of patients.

“We’re not shy about the fact that this is to be part of an internationally prominent program,” he says. “That Bucknell can be involved in something with that kind of impact and reach is pretty exciting.”

The center is one of many collaborative projects between Bucknell and Geisinger Health System, the University’s primary partner in the Human Health Initiative (HHI), one of the six strategic priorities of WE DO, The Campaign for Bucknell University. The initiative includes faculty and undergraduate research in an array of health care-related fields, often performed in conjunction with outside medical experts who work together toward health-care solutions for the wider world.

“Providing everyone access to quality health care has emerged as one of our most urgent national issues,” says President John Bravman. “To our knowledge, no other undergraduate institution has partnered with a major medical center in this way. We’re offering students opportunities to engage deeply, and from many perspectives.”

Bucknell’s strong undergraduate research program offered a glimpse of the potential of expanded health-care research. Funded largely through endowed gifts, it has long provided students with the opportunity to perform research, publish papers with faculty and present at conferences in numerous academic areas. The HHI creates even more opportunities for undergraduate research through strategic partnerships.

The Bucknell-Geisinger collaboration is a natural one, says David Ledbetter, executive vice president and chief scientific officer at Geisinger. “We’re geographically close, we’re two outstanding institutions with different but complementary missions, and we are both committed to community service and benefits. Finding ways we can help each other’s mission to serve the community makes great sense.”

Many projects stem from the Bucknell-Geisinger Research Initiative (BGRI), also housed under the HHI umbrella. Established in 2012, BGRI provides funding to Bucknell professors and Geisinger faculty for collaborations designed to advance health-care research, improve the quality of human health and ultimately lead to external funding.

Professor Dave Rovnyak, chemistry, and Geisinger researcher Brian Irving, for example, won BGRI funding to perform nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis of human serum in a process known as metabolomic profiling. Rovnyak and his students use Bucknell’s powerful NMR instrument to study deactivated samples of serum, which is essentially what’s left of blood after platelets have settled. They’re looking for amino acids or sugars present in different stages of diabetes, with the goal of earlier disease prediction. “The more we can directly work with human samples, the better chance we have of solving medical problems,” says Rovnyak.

Matthew Bailey, the Howard I. Scott Professor of Management, teamed with Geisinger systems engineer Priyantha Devapriya in a BGRI study to examine the flow of patients in the hospital and identify ways to improve efficiency using existing resources. “Recent changes in medical coverage increased the demand on hospitals. The easy solution would be to buy more beds. Instead, we analyzed patterns and ran simulations of different patient caseload scenarios,” Bailey explains. With this data, the duo helped administrators make strategic decisions about resource allocation. They also analyzed surgery sequencing in operating rooms to improve patient care and efficiency.

Other faculty members study different types of data. Professor Brian King, computer science engineering, focuses on bioinformatics, which blends biology and computer science. Through BGRI, he was able to spend a sabbatical doing research with Gerard Tromp, a genomics informatician at Geisinger. They worked to develop tools and algorithms that improve software systems that analyze and manage DNA sequencing. These systems help researchers identify variants in human DNA that are related to disease, enabling earlier treatment.

“One of the things I enjoy most is the synergy created from working with people who have different skills and expertise,” King says. “There’s no one person who can solve disease. It takes a number of people working together — a statistician, a computer scientist, medical experts — to achieve greater solutions to these problems.”

Bucknell hopes that students involved now will become those professionals who make a difference. “Our best measure of success is our alumni,” says Professor Dan Cavanagh, who holds the William C. and Gertrude B. Emmitt Memorial Chair in Biomedical Engineering. “They attend the best graduate schools and go on to careers in industry, medicine, law, business and science. At Bucknell, student outcomes are always the top priority, but if we can improve health care at the same time, everyone wins.”