Nurturing Greatness

January 21, 2015

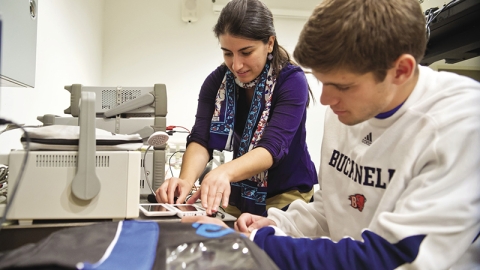

Professor Amal Kabalan, electrical & computer engineering, works with Grant Reynolds ’16. Funding from the C. Graydon and Mary E. Rogers Faculty Fellowship is helping her refine a backpack that stores solar energy.

Faculty fellowships do more than pay for research and equipment. They bring the brightest scholars to Bucknell — and help keep them here.

In her electrical engineering lab at Bucknell, Professor Amal Kabalan works to improve education for children thousands of miles away in Guinea, where political strife has knocked out power to many homes. She’s perfecting a backpack that will store solar energy by day and power lamps by night, allowing students to safely do homework indoors rather than under streetlights.

Kabalan, a first-year professor, started her academic career with an edge. As part of her hiring package, she was offered the C. Graydon and Mary E. Rogers Faculty Fellowship, which provides funding for research, teaching and professional development. The fellowship allowed her to immediately buy equipment and begin testing LEDs and solar panels in her quest to create a high-performance, low-cost backpack. The award sealed the deal to bring Kabalan to Bucknell, which offered her more funding than other institutions.

Kabalan’s story illustrates the power of faculty fellowships, which help recruit and reward the best professors. The awards pay for equipment, research travel, professional conferences, undergraduate researchers and more. Whether endowed by individual donors or funded through annual giving, fellowships raise the level of teaching and scholarship and strengthen the entire University.

The Jane W. Griffith Faculty Fellowship, for example, allowed Professor DeeAnn Reeder, biology, to buy specialized equipment to study bats when she joined the faculty in 2005. “Colleagues who visit from larger schools are just blown away by the caliber of my facilities,” she says. The award also signaled Bucknell’s confidence in her ability and potential. “It was great to know that the University was excited about me being here,” says Reeder, who is known internationally for her research of disease in bats.

Yet another benefit, she notes, is that academic funding attracts more funding. “When you’re applying for grants, foundations want to see evidence of achievement. Having the Griffith fellowship shows that Bucknell has bought into my research and fully supports my program.”

Professor Deborah Sills, civil & environmental engineering, was recruited with a Swanson Fellowship in the Sciences and Engineering, which paid for her lab’s computer, software and databases. She, too, views her award as a foundation for future funding. “It let me dive into a research program without having to track down grants,” says Sills, who studies the conversion of biomass to energy. “This equipment is allowing me to do research that I can leverage into grant applications.”

The recruiting power of fellowships extends beyond newly minted Ph.Ds. A Rogers Award helped Professor Neil Boyd, management, decide to leave a tenured position as chair of business administration at another school to join Bucknell, which hired him in 2013 to support the new Managing for Sustainability major.

“There are risks when you’re coming into a new environment from another institution,” says Boyd. “The fellowship was an incentive that helped tip the scales and draw me to the University.” His funding has helped stimulate what he calls the most productive year to date in his research, which examines how a sense of community and responsibility for an organization translates into better employee engagement, job satisfaction and overall organizational health.

Faculty fellowships also help retain and reward current professors. In 2013, George Shields, dean of the College of Arts & Sciences, sought a way to encourage more associate professors to apply for promotion to full professor. His solution, the Arts & Sciences Dean’s Fellowship, provides funding to help outstanding professors advance to the next level. The Deans’ Funds for the Liberal Arts & Sciences, a designation of the Annual Fund, pays for the awards, which faculty use for research, travel, conferences, new collaborations and other activities that enhance their teaching and scholarship.

“These fellowships invigorate careers,” Shields says. “They’re good for the individual, the department, the college and the University, through the increased prestige of having more full professors. The more heavily we invest in their scholarship, the better their teaching becomes.”

Professor Kevin Myers, psychology, studies appetite, food preferences and obesity with rats in his campus lab. The Dean’s Fellowship allowed him last summer to travel to Kenya, where he began new research with international collaborators. “At the mid-career stage, you’ve established a foundation, so it’s a good time to branch out and develop new expertise,” says Myers, who has also used the funding to collaborate with colleagues in neuroscience.

David Scadden ’75, P’11, a University trustee, believes that active scholars make better teachers and, in turn, better students. He established the David T. Scadden Faculty Scholar Award to encourage greater scholarship among faculty in the arts, humanities and life sciences. “Those are the areas that touched my life most powerfully and where research support can be the hardest to get in a university of our size,” says Scadden, a world leader in stem-cell research.

Professor Matthew Slater, philosophy, used his Scadden funding to convene an interdisciplinary group of faculty and students who share an interest in biodiversity, biological classification and environmental ethics. The resulting series of lunch meetings influenced the content of his most recent book, Are Species Real?, which was central to his tenure package. It also sparked new collaborations and independent student projects.

Professor Matthew Slater, philosophy, used his Scadden funding to convene an interdisciplinary group of faculty and students who share an interest in biodiversity, biological classification and environmental ethics. The resulting series of lunch meetings influenced the content of his most recent book, Are Species Real?, which was central to his tenure package. It also sparked new collaborations and independent student projects.

That’s the kind of outcome Scadden was looking for. “My hope was that projects could move forward, that faculty could engage students and that both would know that their commitment to answering questions was valued by those who are not on campus to tell them so directly. The results could not be more gratifying.”