Where Do We Go From Here?

July 17, 2015

In March, three students were expelled after making racist remarks on air at WVBU. The incident sparked anger, resentment and plenty of soul searching.

In March, three students were expelled after making racist remarks on air at WVBU. The incident sparked anger, resentment and plenty of soul searching.

On a humid Monday morning in May, in that brief, comparatively quiet space between spring semester’s end and Commencement, John Bravman sits in his office in Marts Hall revisiting the most difficult stretch of his tenure. He’s just completed his fifth year as Bucknell’s president, and he cites among his proudest accomplishments a set of numbers — from recent faculty hires and from the incoming first-year class — that show historic progress toward the creation of a more diverse campus. They are the early but tangible payoff of a concerted effort.

“There are some real successes here, and to me, they’re exemplary of what we can do if we really put our minds to it,” Bravman says. “To reach that point, and all of a sudden find that at risk — it was hard. That’s one of the many reasons why this was so difficult.”

This, of course, is the now-notorious campus radio broadcast, an awful moment of brazen hate speech in March that drew national attention and sent tremors through the University community. “N----,” said one student. Then another: “Black people should be dead.” Then a third student, “Lynch ’em.” The words used by those three since-expelled Bucknell students were specific and toxic, so flagrant as to seem almost unreal.

But talking about it now, even as he refers to this “single event,” Bravman is ever mindful of the context: There was shock, of course, even dismay at just how blatant the comments were — but for some, the content of the comments themselves was not surprising.

“To hear things like that when you’re out downtown at night, that’s nothing,” says Danielle Taylor ’17, a leader in both student government and the Black Student Union. “It’s expected.”

An appreciation of that broader context is vital to understanding both the damage done and the opportunity created by that incident this spring. Talk to the president, to faculty members and most importantly to students, and it’s clear that those realities must be considered side by side. Yes, this happened, and no, it wasn’t an anomaly; racism exists at Bucknell just as it does at institutions across the country. Some might argue that racism at Bucknell is exacerbated by a culture that in many areas, and despite many efforts, reinforces existing divisions in the student body. That all of this is true cannot distract from another truth: That this community possesses the tools to do, and be, better.

To look back on the days and weeks that followed the broadcast is to see the progress Bucknell has already made, and to glimpse early steps on a hopeful path forward.

The student response came in stages. First came revulsion, fear and anger, all understandable reactions upon hearing the words uttered by three of their fellow students.

What came next, for many, following Bravman’s initial message to the Bucknell community, was something closer to indignation. That many were reacting to a single line in the email note Bravman sent to the student body — the statement that “this is not who we are” — speaks to the depth and sensitivity of the problem.

“It was the idea that the people who did this are not us, they’re the ‘other,’ so just get rid of them,” Taylor says. “In reality, these people are part of the culture.”

Alex Rosen ’16, president of Bucknell Student Government, says she and members of the BSG talked at length about the incident and reached the same conclusion. “This is us,” says Rosen. “It’s easy to point fingers, but pointing fingers back at ourselves is the only way we’re going to see substantial change.”

This is not who we are. Those words came in the midst of a short, strongly worded message issued the same day the administration learned of the broadcast, a message in which Bravman referred to conduct that was “unacceptable,” “inexcusable” and “detestable,” noted that an investigation was already underway, and confirmed that the students were suspended and that they and any others found culpable might face expulsion. It was a blunt and unequivocal rebuke, but from the perspective of many in the Bucknell community, it seemed somehow not enough.

The days following Bravman’s initial communication to campus brought ample opportunity for all involved to share, and clarify, their perspectives. On the last day of March, Bravman met with students to hear their concerns. Much of what he heard echoed stories he’d been aware of since his arrival. The fresh impact, he says, came from “hearing the way this incident was felt and perceived, and how it was representative of a daily experience for some of our students.

“It’s not just what they say, but how students talk about an event like this, having a sense of how that impacted them. As a caring human, you have to confront that.”

The stories Bravman heard varied, from offhanded comments to threats to the sense of being locked out of the full experience of a Greek-dominated campus social life. What seems clear is that, among Bucknell’s minority students, no one feels immune. “I’ve had experiences where I didn’t feel comfortable, where someone called me the N-word, and I’m the Black kid you come and cheer for on Saturday night,” say Ryan Frazier ’16, a basketball co-captain and well-known campus figure. “If it can happen to me, imagine how it feels for someone just going to school here, someone who came from an inner-city school and has never been around this many white people in his life.”

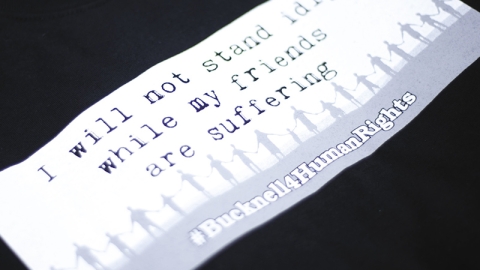

That was the heart of the message that Frazier shared in his well-received speech at a campus solidarity ceremony held in mid-April. Organized by student leaders, the ceremony drew thousands to the Academic Quad. Rosen and Taylor were among the students who spoke that evening, a lineup that Rosen introduced as “your friends, your peers, your classmates, your brothers, your sisters and your teammates — and they deserve to be listened to.”

Carmen Gillespie, a professor of English and the director of Bucknell’s Griot Institute for Africana Studies, says the majority of her white students expressed “shock and despondency” when they heard about the broadcast and consistently responded: “We didn’t know this was happening.”

On this, Frazier’s perspective is at once a compliment and indictment: “One thing I said in my speech is that in my experience, the kids in my school are entirely too smart and entirely too kind not to recognize the problem.”

And yet, there it is — and it’s not only affecting students. Gillespie wears her hair in long dreadlocks, and she recalls walking on Market Street in downtown Lewisburg years ago and hearing someone yell “Medusa!” from a passing car. “As an English professor, at least it was evidence of someone having read some literature,” she says, laughing at the memory now. “Of course I’ve experienced racism here. But I don’t know what it would be like to be an 18-year-old African-American person at Bucknell. You have students who feel besieged, for whom this happens all the time. That’s what we need to address.”

The challenge is being addressed now in unprecedented ways. The approach, necessarily, is multi-pronged, involving parallel efforts from across the campus community. Gillespie describes it as “profound” that the student leaders are taking it upon themselves to effect change. “That doesn’t absolve the faculty from responsibility,” she says, “but I think if Bucknell is going to continue becoming the institution it aspires to be, the students have to conceive and push the agenda. Some of that has to come from them.”

Gillespie also praises Bravman’s willingness to engage the students — and to listen. “I think John’s courage, of taking seriously and communicating publicly about the implications of what was said, was very important,” Gillespie says. “It was an affirmation that racism is not something we can accept as a community.”

Michael James, professor and chair of the Department of Political Science and, like Gillespie, a member of the President’s Diversity Council, similarly praises the students’ actions since March. “The thing that’s so touching, and so humbling,” James says, “is how they’ve said, ‘I won’t be able to experience the improvements that I hope will happen. I’m doing this for the next generation.’ They won’t be here, but they have this sense of trusteeship, that they’re worried about the next generation of students. That same level of trusteeship is the sort of ethos that we need from the people who can make changes.”

James and Gillespie are among the faculty members interested in possible changes or additions to the University’s core curriculum. Many professors found ways last semester to tie the topic of discrimination into their classroom discussions, and whether it’s a required class or a common text for new students, or perhaps something tied into fall orientation, there is a push to bring diversity issues more formally into the educational experience. Bravman notes that, “There’s no directing from the top on a new curriculum. It really has to rise organically with the faculty, who own the curriculum.”

In the areas directly within its control, the administration is building on a number of new and existing initiatives. Bridget Newell, hired in 2012 to fill the newly created role of associate provost for diversity, oversees diversity issues in faculty and staff recruitment and retention, curriculum and community involvement. Newell also sits on the 12-member President’s Diversity Council, which was convened in 2012 as the first such council at Bucknell; at press time, the council was due to present its first annual report on the council’s Diversity Strategic Plan.

Bravman also emphasizes the role of diversity in the University’s strategic plan, which was approved in 2006. He notes that the Board of Trustees recently (and unanimously) reaffirmed the plan, of which one of the five pillars is the stated goal of enhancing diversity. “There’s really quite broad support among the trustees for wanting to do better, and charging me with making sure we do do better,” Bravman says.

And then there are the numbers: For the incoming class of 2019, non-international students of color account for nearly 23 percent, a 55 percent increase over the previous class and by far the most diverse in Bucknell’s history. Of 24 full-time faculty hires in the most recent hiring cycle, fully 13 — nine of 18 in the College of Arts & Sciences, four of six in the College of Engineering — come from groups that are underrepresented at Bucknell. And following conversations spurred by the broadcast, the University authorized three additional faculty hires and a two-year post-doctorate position in Africana studies. “For a school of our size,” Bravman says, “that’s a major commitment.”

It will be more difficult to measure such progress in another area, one that is widely cited as inseparable from the climate issues at Bucknell: social life on campus. “Greek life is big,” Frazier says. “If you’re in a fraternity, and it’s a Friday or Saturday night, that’s where you are.” The dominance of a Greek system that is overwhelmingly white is an entrenched and problematic issue. As a prominent athlete, Frazier says being left out of social activities generally isn’t a problem for him, but he knows that a general sense of “feeling unwelcome” is an issue many of his fellow students face.

Taylor says she’s long joked about transferring, largely because of the challenges of fully engaging in the campus social scene. “Bucknell is a great place, the education is amazing, and when I leave here I know so many doors will be open for me,” she says. “But as far as fun — it’s not the most fun.” It might sound like a frivolous concern, until it’s contrasted with the fact that for many Bucknell students, “fun” — really, the full experience of being a college student — is something they’re able to take for granted without ever stopping to consider it.

Bravman cites the difficulty of forcing progress on what are by nature self-selecting organizations, and he’s aware that the sheer numbers — more than half of Bucknell’s seniors will graduate as Greeks — means systemic change is a daunting challenge. He acknowledges that the Greek system is “seen by many as a bastion of separatism, and I would certainly like to see the demographics more closely match the changing demographics of the student body. We will work hard to find ways to realize that.”

It’s a statement that will — that must — apply to the broader effort at Bucknell, and there is optimism that it will. “I’m completely optimistic,” Bravman says. “There are a lot of really good people here who want to make progress, and I think we can use this as a catalytic moment. I believe this is a moment in which we can take a stand, not just against racism, but against sexism, homophobia, transphobia — all forms of discrimination that too often confront members of our community.”

In that, he’s not alone. “I think we’ve hit a turning point in Bucknell’s history,” Taylor says, “and the inspiring part is that it’s not just students of color coming together. It’s a diverse group saying, ‘Hey, we need to come together to make this better.’”

Adds Rosen, “With the summer here, there’s a fear that the momentum’s going to stop. But I’m optimistic that, because the response was so powerful, people aren’t going to let it.”

“I’ve only been here seven years, but even in talking to colleagues who’ve been here a long time, there is a sense that this has the potential to be a profoundly significant moment in Bucknell history,” says Gillespie. “But the bottom line, and what I always ask the students — especially underrepresented students — is this: If you had to do it over again, would you still come to Bucknell?”

The answer, she says, has been universal: Yes, we would.The next step, Gillespie says, is ensuring they don’t have to qualify their answers. When students, regardless of color or any other difference, have no doubt they’re in the right place, the University can be confident that it’s in the right place, too.

Ryan Jones is a senior editor at The Penn Stater magazine and the former editor-in-chief of SLAM Magazine.